the odyssey

It was a long overdue debt with “literature.” A checkmark on a list of titles that the scholarly-bent reader thinks is required to enter the dignified club of literarte.

(July 9, 2017)

there is nothing I can add to what has already been written about The Odyssey, and there is little I can say about my reading this classic poem. It was a long overdue debt with “literature.” A checkmark on a list of titles that the scholarly-bent reader thinks is required to enter the dignified club of literarte.

One week of vacation began this Monday. In a spreadsheet, I estimated, as realistically as possible, the number of hours I would have to dedicate to the basics: fitness (strength training, mobility, stretching, trail running, tennis), socializing, housekeeping, cooking, time-wasting, etc. I was left with 28 hours of available time, or approximately 600 pages to read. On the list of candidates: War and Peace, The Rambler (Johnson), Byzantium (Folio Society), The Remains of the Day (Ishiguro), Zen and Japanese Culture (Suzuki), The Aeneid, and some others.

But The Odyssey, with its 400 pages and friendly translation by Robert Fagles won the raffle.

pity

I couldn’t pity Odysseus because I knew his destiny already. I felt sad, however, for Calypso and her mournful protest when Hermes flies to Ogygia to communicate the decree of the gods: release Odysseus and let him sail back to Ithaca.

Hard-hearted

you are, you gods! You unrivaled lords of jealousy-

scandalized when goddesses sleep with mortals,

openly, even when one has made the man her husband.

So when Dawn with her rose-red fingers took Orion,

you gods in your everlasting ease were horrified

till chaste Artemis throned in gold attacked him,

out on Delos, shot him to death with gentle shafts.

And so when Demeter the graceful one with lovely braids

gave way to her passion and made love with Iasion,

bedding down in a furrow plowed three times-

Zeus got wind of it soon enough, I’d say,

and blasted the man to death with flashing bolts.

So now at last, you gods, you train your spite on me

I was also moved by the image of involuntary tears rolling down Telemachus’s face when, at Menelaus’s palace, the king of Sparta remembered his comrades of battle, and in mentioning Odysseus, he wondered “how they must mourn him too, Laertes, the old man, and self-possessed Penelope. Telemachus as well, the boy he left a babe in arms at home.”

meditation | olympus

When Odysseus is washed up on the beaches of Phaeacia, there is a passage that describes Olympus that could as well be applied to describing how I feel during meditation:

The bright-eyed goddess sped away to Olympus, where,

they say, the gods’ eternal mansion stands unmoved,

never rocked by gale winds, never drenched by rains,

nor do the drifting snows assail it, no, the clear air

stretches away without a cloud…

Unmoved, clear, calm, present.

on the simple life

And when, in the same island of Phaeacia, Odysseus was taunted by young Laodamas to participate in their games, and Odysseus, unable to vanquish his pride, throws the discus the farthest and proclaims that no one in the island can beat him, Phaeacia’s king Alcinous thoughtfully replies:

…nothing you say among us seems ungracious.

You simply want to display the gifts you’re born with…

We’re hardly world-class boxers or wrestlers, I admit,

but we can race like the wind, we’re champion sailors too,

and always dear to our hearts, the feast, the lyre and dance

and changes of fresh clothes, our warm baths and beds.

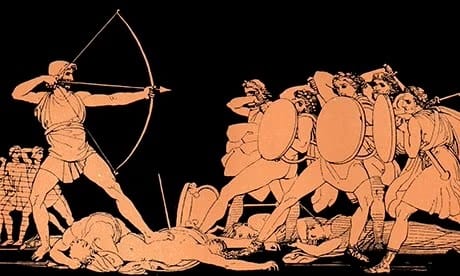

on the brutality of war

In a banquet in the palace of king Alcinous, a harper’s singing reminds Odysseus of the realities of battle, and the hero weeps with heartbreak.

… as a woman weeps, her arms flung round her darling husband,

a man who fell in battle, fighting for town and townsmen,

trying to beat the day of doom from home and children.

Seeing the man go down, dying, gasping for breath,

she clings for dear life, screams and shrills-

but the victors, just behind her,

digging spear-butts into her back and shoulders,

drag her off in bondage, yoked to hard labor, pain,

and the most heartbreaking torment wastes her cheeks.

the sirens: disappointment

The famous passage of the Sirens, much dramatized in today’s culture, citing the gut wrenching cries and commands of Odysseus to his crew to unfasten him from the mast, occupies but two stanzas in the poem. And it is not tainted with exaggeration, aggrandizement, or melodrama. Two stanzas, 28 verses, and off to the next evolution: Scylla the monster with six heads, and Charybdis, the whirlpool.

poseidon: vengeful, megalomaniac, and evil

Throughout the book, and perhaps Greek mythology in general, Poseidon reminded me of the god of the Old Testament. Insecure, ruthless, megalomaniac, capricious, evil. God of the earthquake. He is the one who sentenced Odysseus to exile in Ogygia. And when, at last, Odysseus plants foot in Ithaca, thanks to the generosity and good will of the Phaeacians, Poseidon throws a fit, almost like a man-child.

“… I’d like to avenge myself at once, as you advise...

I’ll crush that fine Phaeacian cutter

out on the misty sea, now on her homeward run

from the latest convoy. They will learn at last

to cease and desist from escorting every man alive-

I’ll pile a huge mountain round about their port!"

the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth

When Odysseus arrives at his own palace, still disguised as a wandering old vagrant, and claims to have heard about long gone King Odysseus, Penelope calls him to her room to hear what he has to say about her missing husband. “I have heard” he said, “that Odysseus now, at last, is on his way…” and he proceeded to tell her about the cattle of the Sun, the land of the Phaeacians, the death of his crew… but, shrewdly, he forgot to tell her about his messing about with Calypso. He didn’t lie, he just did not tell the whole truth.

To his credit, many pages later, once he revealed as Odysseus himself, he narrated the whole truth to Penelope.

the elements

Homer, when describing characters or objects of great strength, many times refers to the main elements of wind, fire, and water. Not earth. In this passage, in Parnassus, Odysseus the boy is out hunting with his grandfather:

Then and there

a great boar lay in wait, in a thicket lair so dense

that the sodden gusty winds could never pierce it,

nor could the sun’s sharp rays invade its depths

nor a downpour drench it through and through

women in the old days

Not surprisingly, misogyny, slavery, and terror of the gods pervades the book. How curious to find these three friends altogether once more in the infancy of our species!

Penelope takes the stage and scolds her suitors for not permitting the old beggar (Odysseus) to test his strength with the bow and string. A moment later, her son, Telemachus, cuts in with these telling words:

“… So, mother,

go back to your quarters. Tend to your own tasks,

the distaff and the loom, and keep the women

working hard as well.”

on the good death

The last book, Peace, contains two episodes that could be prescindible. There is the entry of the dead suitors into the house of the dead, where they find Achilles and Agamemnon. And there is also the unnecessary deceiving of Laertes by Odysseus, why pretend not to be his son? The man is old and beaten already, why play tricks on him?

But back in the house of the death, Agamemnon remembers the magnificence of Achilles’s funeral, and Achilles laments the fate of his friend: good death eluded him.

“But you [Agamemnon] were doomed to encounter fate so early,

you too, yet no one born escapes its deadly force.

If only you had died your death in the full flush

of the glory you had mastered-died on Trojan soil!

Then all united Achaea would have raised your tomb

and you’d have won your son great fame for years to come.

Not so. You were fated to die a wretched death.”

—

And so it goes. Aeneas awaits...